GOVERNMENT CRACKS DOWN ON DISSIDENTS, IGNORES HUMAN RIGHTS

By Andrew Lam

San Jose Mercury News

Article Launched:05/06/2007 01:41:38 AM PDT

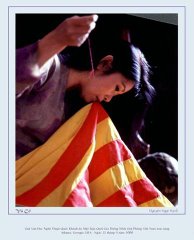

A picture paints a thousand words, but an image taken from the state-controlled television in Vietnam and circulated widely on the Internet can convey the struggle of an entire people. The image shows a man, flanked by two angry-looking policemen, sitting bleary-eyed, his mouth covered by the hand of an out-of-uniform policeman behind him.

Name: The Rev. Nguyen Van Ly. Sentence: Eight years imprisonment. Crime: Carrying out propaganda against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

During his trial March 30, the Rev. Ly's mouth was physically muzzled after he recited four lines of his own poetry.

Communist trial of Vietnam

A lewd comedy for years

Jurors a bunch of baboons

Servants of dictators, who are you to judge?

International human rights groups condemned the sentencing, which took only five minutes; he was not represented by a defense lawyer. "This sentence means Father Ly will be a prisoner of conscience for the fourth time in two decades," said Tim Parritt, Amnesty International's deputy Asia Pacific director. "It is indicative of a broader crackdown on dissent by the Vietnamese authorities that has been intensifying since the country held the APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) meeting last November."

Vietnam intermittently plays a cat-and-mouse game with its political dissidents, arresting and releasing its most famous activists while those less visible are "disappeared." Since March, however, Vietnam has launched one of the worst attacks on dissidents in 20 years. Among those arrested with the Rev. Ly were Nguyen Van Dai and Le Thi Cong Nhan. All three were charged with carrying out propaganda against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, under article 88 of the penal code. If convicted, Nhan and Dai face sentences of up to 20 years in prison.

The arrest and subsequent disappearance of lawyers Le Quoc Quan and Tran Thuy Trang, however, are particularly alarming. Both are well-known. After returning from a fellowship at the National Endowment for Democracy in the United States, Quan was arrested March 8 and charged with attempting to overthrow the Hanoi regime. The day before, Trang, another young lawyer in Ho Chi Minh City, was reportedly arrested by 60 security police officers. She has not been heard from since. According to Human Rights Watch, Trang's family was forced to sign documents promising not to discuss the arrest.

Speculations abound. Why now? Vietnam, after all, has been granted membership in the World Trade Organization and made its entrance to the world's economic stage last November when it hosted its first APEC conference. Its gross national product has been growing at a steady and impressive 7 percent for the last several years, and while political dissent is not allowed, Vietnam's population is experiencing far more personal freedoms than during the Cold War. Many are allowed to travel overseas. Private capitalism is all the rage. Movement within Vietnam is permitted freely. There's a middle class with disposable income and access to the Internet. Vietnamese media, too, while still controlled by the state, have proliferated and some have been pushing the envelope to cover stories of corruption and even official wrongdoings.

Keeping a grip on power

Perhaps that's precisely why, at least in the eye of the ruling communist elites, the crackdown seems to be needed: to maintain absolute power. Political movements are brewing along with an increasingly wealthy and educated population, especially now that the population is growing more sophisticated and politically aware. Voices of dissent are heard daily, if not on the opinion page, then at least on the streets.

Nguyen Van Dai, an outspoken dissident, is one of a handful of practicing human rights lawyers in Vietnam. He founded the Committee for Human Rights in Vietnam in 2006 and was recently awarded the prestigious Hellman/Hammett prize for persecuted writers.

The Rev. Ly is a co-founder of Bloc 8406 - a political movement that made its entrance to Vietnam's public stage on April 8, 2006, when it published "Manifesto for Freedom and Democracy." Two days earlier, it had issued an "Appeal for Freedom of Political Association." These documents boldly challenged the Vietnamese government to uphold individuals' rights to free expression, association and participation in political affairs.

Hanoi swiftly retaliated against both. "Several key organizers of Bloc 8406 and their families have been harassed and imprisoned, showing that the Vietnamese government is still trying to silence its critics," said Sophie Richardson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch. "Targeting the most vocal, visible activists sends a message to the others: Don't speak out or you'll suffer the same fate."

If Hanoi was reluctant to act before President Bush's visit during the APEC meeting last November, it has not hesitated since. For a president who touted "freedom" and "democracy" in the Middle East, Bush came bearing an unexpected gift - a license, as it were - for the government to use against its dissidents. Though the U.S. president originally had hoped to give Vietnam normal trading status, that deal was delayed in Congress. Embarrassed by having no gift in hand, he dropped Vietnam from the list of nations that severely curtail religious freedom instead, even as these violations continued unabated.

The widely published photo of Bush smiling amicably under the bust of Ho Chi Minh augured terribly bad feng shui for Vietnamese human rights activists. It clashed with images of heavily guarded homes of political dissidents just a few kilometers from the APEC meeting in Hanoi. Freedom and democracy, apparently, were far from the U.S. president's mind in Vietnam. The United States once served as the bright and shiny model of democracy for many in Vietnam. But no longer.

Since Bush's visit, the list of those arrested has grown. Nguyen Tan Hoanh, Doan Van Dien, Doan Huy Chuong, Tran Thi Le Hong, Le Ba Triet and Nguyen Tuan are among hundreds of political and religious prisoners in Vietnam, including cyber-dissident Nguyen Vu Binh, at least nine members of the Cao Dai religion, 10 Hoa Hao Buddhists and more than 350 ethnic minority Christian "Montagnards" from the Central Highlands. The latest to be taken into custody on April 21 was Tran Khai Thanh Thuy, an award-winning journalist and writer. Thuy was taken away from her home where she was under house arrest for allegedly violating article 88 of Vietnam's criminal code. What she actually did was writing various essays on the Internet calling for greater democracy.

Congressional resolution

On April 27, 2007, a resolution proposed by Republican Rep. Chris Smith was passed. It says the United States should "make a top concern the immediate release, legal status and humanitarian needs" of the Rev. Ly, and the lawyers Nguyen Van Dai and Le Thi Cong Nhan. The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom on Wednesday likewise recommended to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice that Vietnam be put back on the list of "countries of particular concern," or CPCs. But it may prove to be awkward for Rice - to take back the president's gift in less than half a year.

In Vietnam the word censorship is the colloquial phrase: bit mien - to cover the mouth. The picture of the Rev. Ly's muzzling seems a literal enactment of an old cliche. But in the old days, his image wouldn't have gotten out of the country so quickly or circulated so widely, nor would his voice be heard at all. Back then, before the Cold War ended, he would have disappeared without a trace.

The wind of change seems to be on the dissidents' side. Thanks to high-tech communications such as the Internet, cell phones and satellite dishes, and increasing interactions with foreigners, Vietnam has a more informed, and therefore, increasingly restless, citizenry.

The Vietnamese word for leader - "lanh dao" - literally means "bearer of the truth (or the way)." Such leadership is non-existent among communist party leaders since Ho Chi Minh. These days, the carriers of the dao are identified with dissidents like the Rev. Nguyen Van Ly and human rights lawyers like Nguyen Van Dai and Le Thi Cong Nhan, prisoners of conscience with fearless spirit and indomitable strength.

And so, if one were to peel away the policeman's hand from the Rev. Ly's mouth, the rest of his poem may go something like this.

You can cover our mouths, blind our eyes

We will still speak, and see

Your rotten ideology is at an end

Your cruelty the sign of weakness

Change is coming! Change is coming!

And we, the people, will be free.

Freedom of Speech Under Communism

Favorite Videos

We Will NEVER Forget.....

Favorite Links

Gone...but not forgotten.

Why this Blog?

There are 2 main reasons for this site:

1) There are many young Vietnamese who care about issues concerning Vietnam and the Vietnamese Diaspora, but cannot, or are not very proficient, at reading Vietnamese. Therefore, this site compiles and disseminates these news in English, so that the new generation of Vietnamese around the world can become more aware and, thus, closer to issues in the homeland.

2) Young Vietnamese have many ideas, many differing views on the prospects to democratize and develop Vietnam. The argument for peaceful development verses demands for justice and human rights. Which comes first? Can a civil, peaceful society be built without foundations of social justice?

These are the issues YOU can debate on this site. But remember, say what you mean, and mean what you say, but don't be mean when you say it.

1) There are many young Vietnamese who care about issues concerning Vietnam and the Vietnamese Diaspora, but cannot, or are not very proficient, at reading Vietnamese. Therefore, this site compiles and disseminates these news in English, so that the new generation of Vietnamese around the world can become more aware and, thus, closer to issues in the homeland.

2) Young Vietnamese have many ideas, many differing views on the prospects to democratize and develop Vietnam. The argument for peaceful development verses demands for justice and human rights. Which comes first? Can a civil, peaceful society be built without foundations of social justice?

These are the issues YOU can debate on this site. But remember, say what you mean, and mean what you say, but don't be mean when you say it.

Blog Archive

-

▼

2007

(106)

-

▼

May

(21)

- Vietnamese-American activists call for US to press...

- Bush meets Vietnamese-American opponents of Hanoi ...

- NEWS ALERT: Vietnam Police Kill Christian Prisoner...

- Internet Is ‘New Frontline’ In War For Human Rights

- Fight for the right to choose in Vietnam

- Vietnam elects assembly members

- EU condemns jailing of activists in Vietnam

- Vietnam crackdown on human rights sparks call to a...

- U.S. Condemns Vietnam, Syria for Detaining Politic...

- Vietnam dissident lawyers jailed

- Vietnam Sentences Dissident Lawyers to Prison

- Activists sentenced in Vietnam

- Three activists jailed in Vietnam

- International Community Called to Scrutinise Human...

- Vietnam's vise on dissent

- Dissidents face trials in Vietnam

- International Community Called to Scrutinise Human...

- Memo to Hanoi

- Distorted Headlines: Vietnam's Suppression of Info...

- Blacklist Vietnam for abuse of religious freedom: ...

- House Passes Smith's Resolution Calling for Human ...

-

▼

May

(21)

No comments:

Post a Comment